![]()

When the Child Support Income Cap Isn’t the Cap: Understanding Child Support in High-Income Cases

Summary:

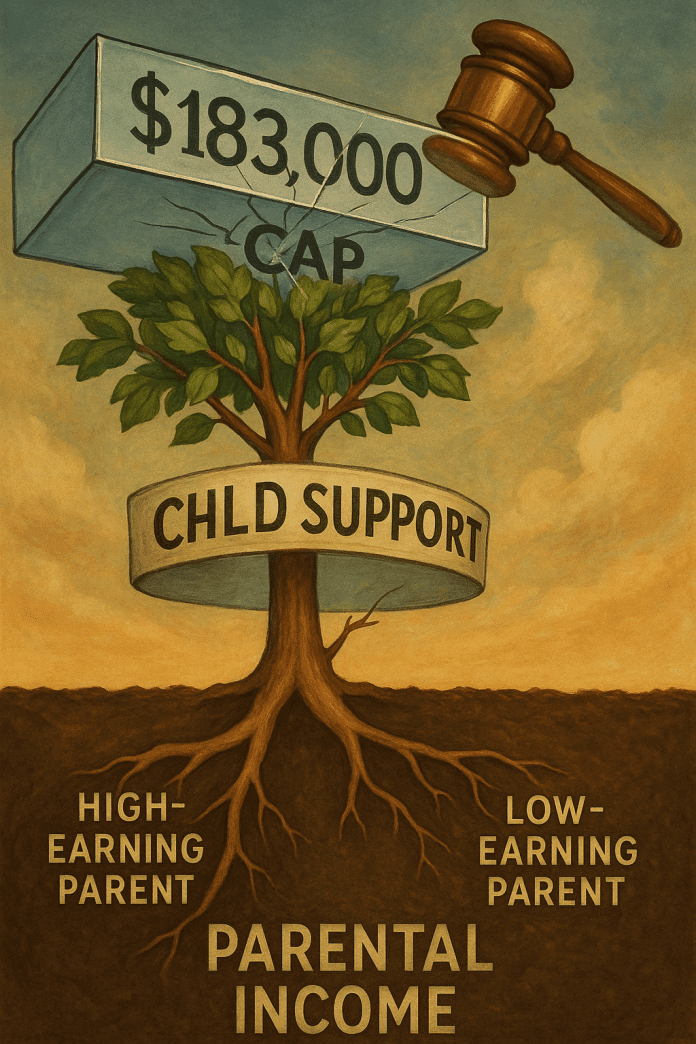

The Child Support Income Cap can set the upper limit on a parent’s income for child support. In New York, child support is calculated under the Child Support Standards Act (CSSA), which applies a set percentage to combined parental income—up to a statutory cap. That cap is currently $183,000. But don’t let that number fool you. If one parent makes significantly more than the other, the court may (and often does) go above the cap. This article breaks down the legal rules, the flexibility the courts have, and the real-world factors that influence support awards—especially in high-income cases.

Table of Contents

Let’s talk about the child support cap in New York. It’s $183,000 as of now, and yes, it goes up every couple of years, like clockwork. But if you think that number is some kind of ceiling, let me assure you: it’s more of a suggestion.

Child support in New York is governed by the Child Support Standards Act, found in both the Domestic Relations Law and the Family Court Act (specifically FCA § 413). The law sets percentages—17% for one child, 25% for two, and so on—to be applied to the combined parental income, up to the cap. What happens above that number is where things get interesting.

The Big Question: When Do Courts Go Over the Child Support Income Cap?

Let’s say Dad earns $200,000, and Mom earns $70,000. Do we stop at $183,000, or do we keep going?

Technically, the statute lays out ten factors the court should consider before applying child support percentages to income above the Child Support Income Cap. But here’s where it gets tricky. In 1995, the Court of Appeals issued a decision in Cassano v. Cassano that turned the statute on its head. The court said, in plain terms: “We don’t have to use the factors to go above the cap. We can just do it.”

So now, judges have two choices: apply the percentages to all income without further explanation, or explain why they’re going above the cap using the statutory factors. Either approach is legally sound.

I’m not here to argue whether Cassano was rightly decided—that ship has sailed. It’s the law, and unless the Court of Appeals or the Legislature changes it, we live with it. What I can tell you is how this plays out in real life.

Real Numbers, Real Cases

Let me give you a real-world example. I had a client making $1 million a year. His spouse made $35,000. They had three children. She wanted child support calculated on his full income. We offered to apply the percentages to $350,000—well above the $183,000 Child Support Income Cap. That would’ve meant $101,500 a year in tax-free support. Not chump change. She still wanted more. Even the court suggested our offer was more than fair. Eventually, a deal was made—but it took time and plenty of negotiation.

That’s the thing with high-income cases: nobody really believes the court is going to freeze child support at $183,000 if there’s a massive income disparity. And frankly, in settlement talks, we often breach the Child Support Income Cap without blinking. It’s not about what the law says in theory; it’s about what feels equitable in practice.

Let’s Do the Math

Here’s a classic example. Dad makes $100,000. Mom makes $40,000. Two kids. Combined income = $140,000.

Using the cap ($183,000), we’re under it, so we apply 25% to the full $140,000 = $35,000.

Now we apportion that support obligation. Dad earns 71% of the income. So he pays 71% of $35,000 = $24,850.

But what if we used just Dad’s income? 25% of $100,000 = $25,000. Not much difference. But the equation shifts when income increases dramatically.

Courts Can Apply the Cap—But Don’t Count on It

I’ve had cases where the court decided not to go over the cap. One father showed he was involved—picked the kids up, cooked dinner, bought clothes, paid half the extras, took the kids for haircuts (this made a big impression on the judge). The mother, on the other hand, had been taking the tax credit and didn’t show she needed more support. The court held the line and didn’t go above the old cap (it was $130,000 back then).

Contrast that with another case where the father made the same arguments, but didn’t back them up with concrete examples or financial contributions. The court blew past the cap without hesitation.

The lesson? If you’re the non-custodial parent and want to keep support under the cap, you’d better show up—literally and figuratively. Judges want to see involvement, consistency, and fairness.

What It Means for You

If you’re negotiating support or headed to court, know this: the $183,000 cap is not a wall. It’s more like a speed bump. The higher the income disparity, the more likely the court is to apply the full statutory percentages to income well beyond that figure.

But it’s not a guarantee. With the right facts, strong documentation, and a reasonable request, it’s still possible to keep support within limits. As always, the key is preparation—and understanding that the law allows for a wide range of outcomes.

FAQ: High-Income Child Support in New York

What is the current child support cap in New York?

As of now, it’s $183,000. But that number is adjusted every two years.

Can the court go above the cap?

Yes. The court can apply the child support percentages to all income or explain why it’s going over using ten statutory factors. It’s their call.

What are those 10 factors?

They include things like the child’s needs, standard of living, tax consequences, educational costs, and each parent’s financial resources. But courts don’t have to cite them if they choose to apply percentages straight through.

If I make $200,000 and my ex makes $50,000, will the court go over the cap?

Probably. Especially if you’re the non-custodial parent. The larger the gap, the more likely it is.

Can I negotiate a cap above $183,000?

Absolutely. In settlements, we often set a higher cap that still reflects the statutory percentages. That allows for predictability and fairness.

Can a judge decide not to go over the cap?

Yes—but usually only if the non-custodial parent is actively contributing to the kids’ lives and finances in ways beyond just writing a check.

![Do I Have to Pay Child Support if I’m Not the Biological Father? The 3 Critical Facts [2025 Legal Guide] Metaphorical picture of the child support obligation when a perosn is not the biological father.](https://nydivorcefacts.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Estoppel.png)

![The Critical Factors On How Domestic Violence Affects Child Custody and Visitation Rights in NY [2025 Guide] Domestic violence affects Child Custody](https://nydivorcefacts.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/a3295ac6-eaea-4c38-901c-4d8562f852e5-218x150.png)